Text

The Norwegian writer Knut Hamsun combines brilliance and profound low points, culture and barbarism to an extreme extent: he is an alluring writer who grew up in the second half of the 19th century surrounded by poverty and bigotry and subsequently became one of the leading protagonists of modernist literature, admired by Kafka, Miller and Joyce. And yet he was also an overt Nazi, who gave his Nobel Prize medal to Goebbels, made a pilgrimage to visit Hitler at Obersalzberg and wrote an infamous obituary of him in 1945, remaining politically blinded to the end of his long life. A delight in provocation, transgression and excess are as much part of his life as his literature and both carry within them sharp, irreconcilable contradictions that we can still see today.

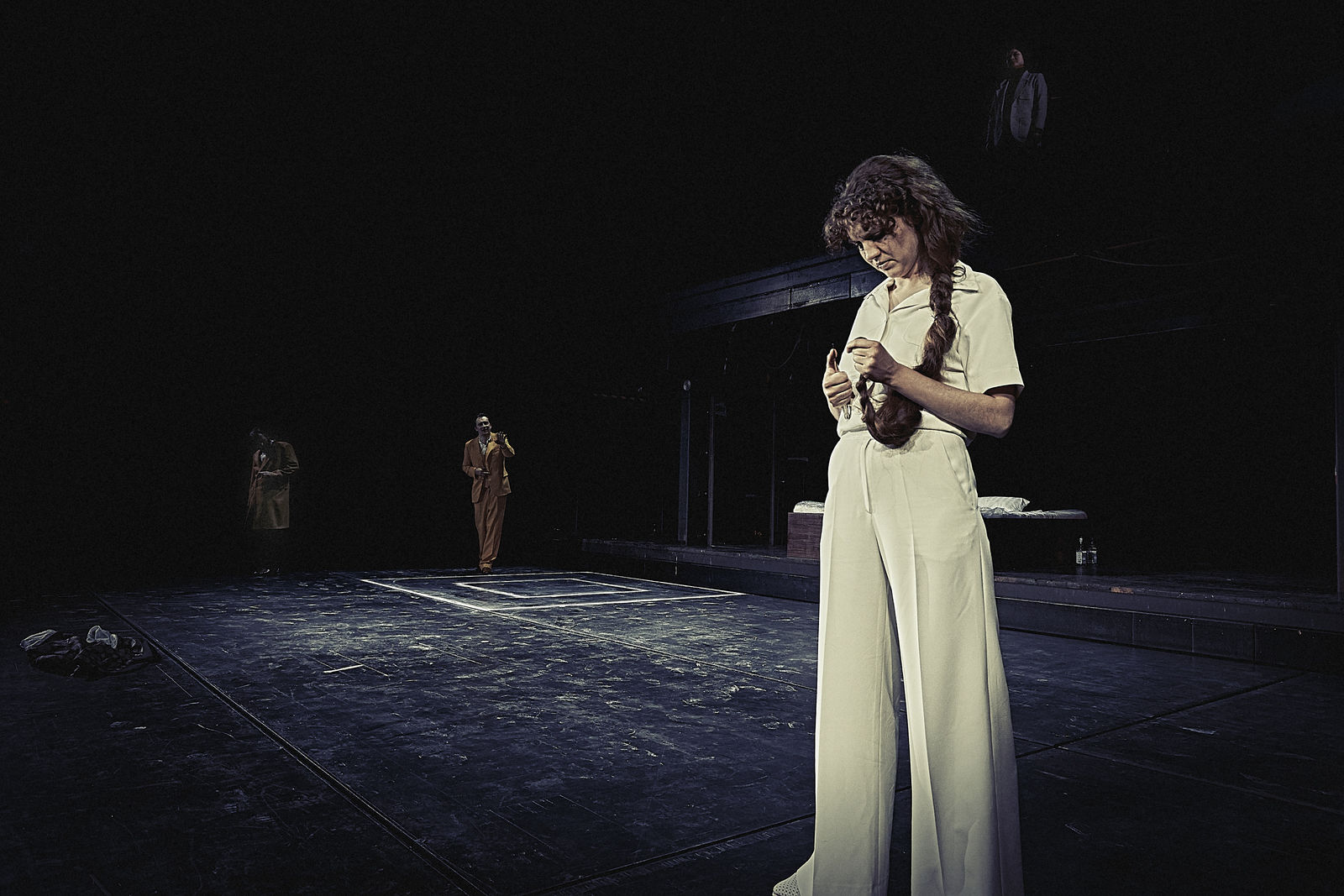

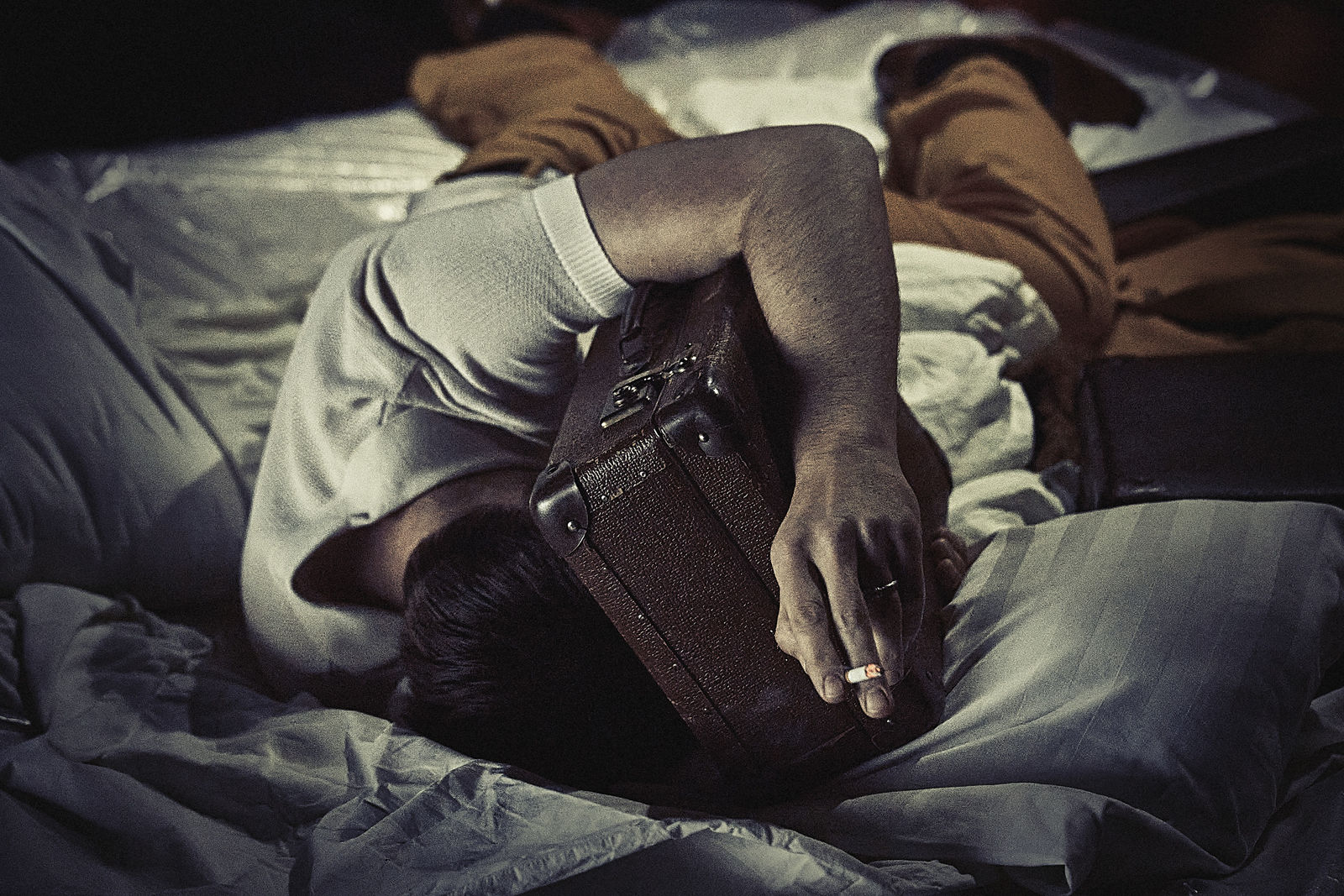

Hamsun’s novel Mysteries (1892), which followed his more famous novel Hunger that established Hamsun’s literary reputation, is an energizing, remorseless, delirious book. A mysterious stranger, a man called Nagel, turns up in a Norwegian port wearing a bright yellow suit and with a violin case under his arm that turns out to be full of dirty laundry and with an iron ring on his finger that he believes possesses miraculous powers. He attracts attention wherever he goes, though people never really know where they are with him: he is contradictory, unorthodox, immoderate. He makes friends with the local oddball, called Minute, who he protects from bullies and gives money to, even though he believes he is a murderer. He falls unwelcomely in love with the newly-engaged pastor’s daughter, killing her beloved dog. He makes a great show of buying a worthless chair for a large sum of money from a woman who is no longer young and then proposes marriage to her. He throws his money around while claiming he has none. He is always on the go and his hand is constantly on the trigger: his thoughts are like arson attacks on what the citizens of this small town see as common sense – nothing is safe from him: science and liberalism, the mediocrity of supposedly great men and the despised masses. He is constantly self-dramatising, calculating and miscalculating and laying himself bare. He keeps cyanide in his jacket pocket, ready at all times, but his attempt at suicide fails. In the end he jumps into the sea after throwing his ring away into it.

The mysteries of the novel’s title “announce themselves like a blizzard of great power”, as one of Hamsun’s contemporaries put it: an ego is let loose here, disorientated amid the world’s myriad symbols, driven by the ancient and modern question: what can we hold on to in order to survive? Science? Faith? Lies (are they lies)? The community? Violence? Love? In the end we are left searching for salvation – from loneliness, from guilt and from ourselves.

Knut Hamsun: Mysterier

Copyright © Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AAS. 1892 [All rights reserved.]

Information about the piece

- Mysterien

- after Knut Hamsun

- from the Norwegian by Siegfried Weibel

Adaption by Angela Obst - Director: Johan Simons

- With: Guy Clemens, William Cooper, Sachiko Hara, Karin Moog, Anne Rietmeijer, Steven Scharf, Jing Xiang

- Duration: 3:00h, eine Pause

- Premiere: 17.09.2021

- Language: German with Englisch surtitles

Video content

(c) Siegersbusch Film

Participants

- Director: Johan Simons

All people

- Director: Johan Simons

- Translation: Siegfried Weibel

- Theatre version: Angela Obst

- Stage design, Costume design: Anja Rabes

- Composition: Carl Oesterhelt

- Sounddesign: Will-Jan Pielage

- Light design: Jan Hördemann

- Video: Florian Schaumberger

- Dramaturgy: Angela Obst

- With participation of: Musiker*innen der Bochumer Symphoniker

- Conductor: Magdalena Klein

- Violin: Raphael Christ, Iwona Gadzala, Christiane Gurung, Jiwon Kim, Ursula Lee, Esiona Stefani

- Viola: Marko Genero, Almud Philippsen, Aliaksandr Senazhenski

- Violoncello: Dimitrij Berezin, Christof Kepser, Wolfgang Sellner

- Contrabass: Asako Tedoriya

Cast

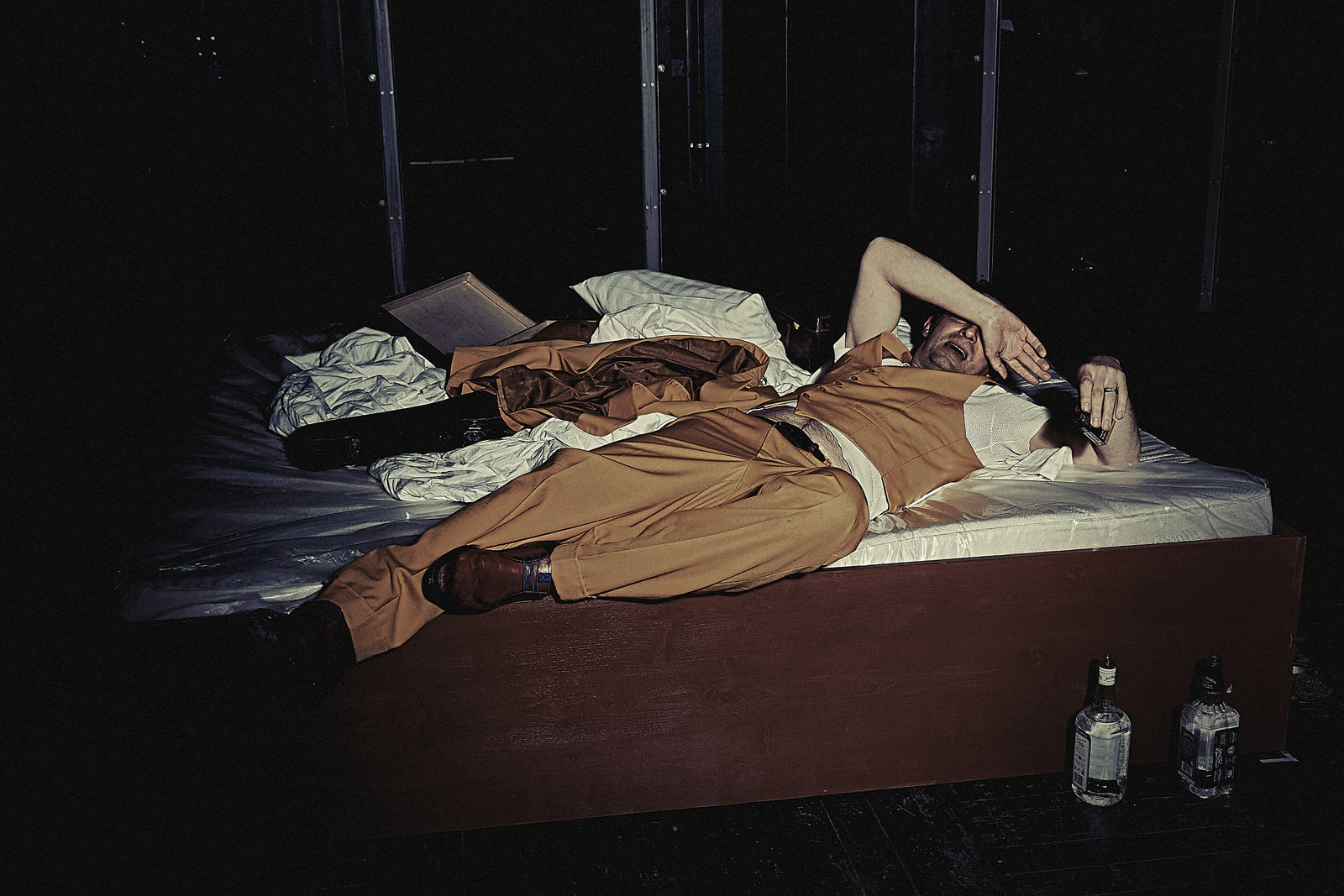

- Johan Nielsen Nagel: Steven Scharf

- Johannes Grøgaard: Guy Clemens

- Dagny Kielland: Anne Rietmeijer

- Martha Gude / Kamma: Karin Moog

- Doktor Stenersen: Jing Xiang

- Bevollmächtigter: William Cooper

- Piano: Sachiko Hara

Images

Steven Scharf, Anne Rietmeijer (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

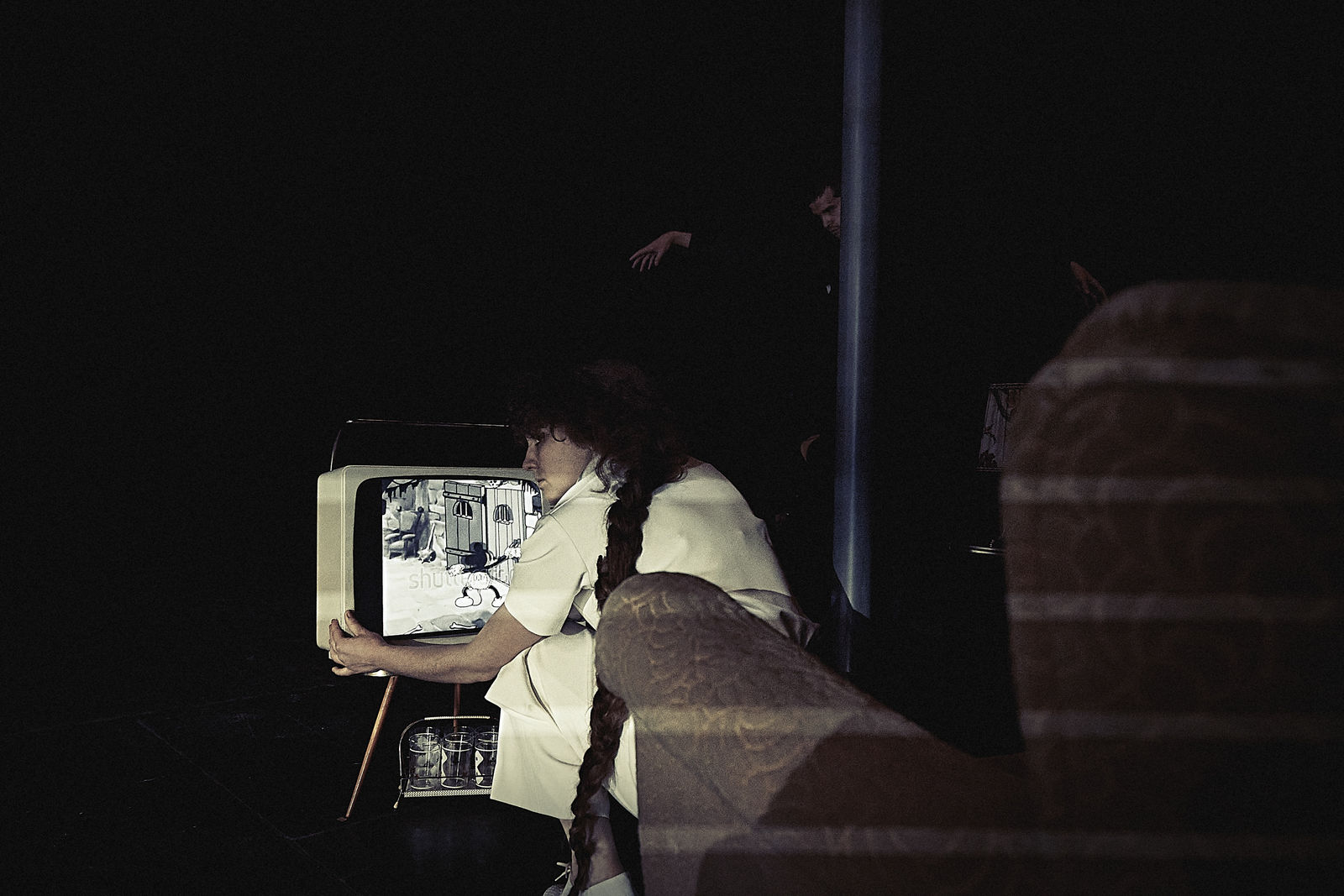

Steven Scharf, Karin Moog (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

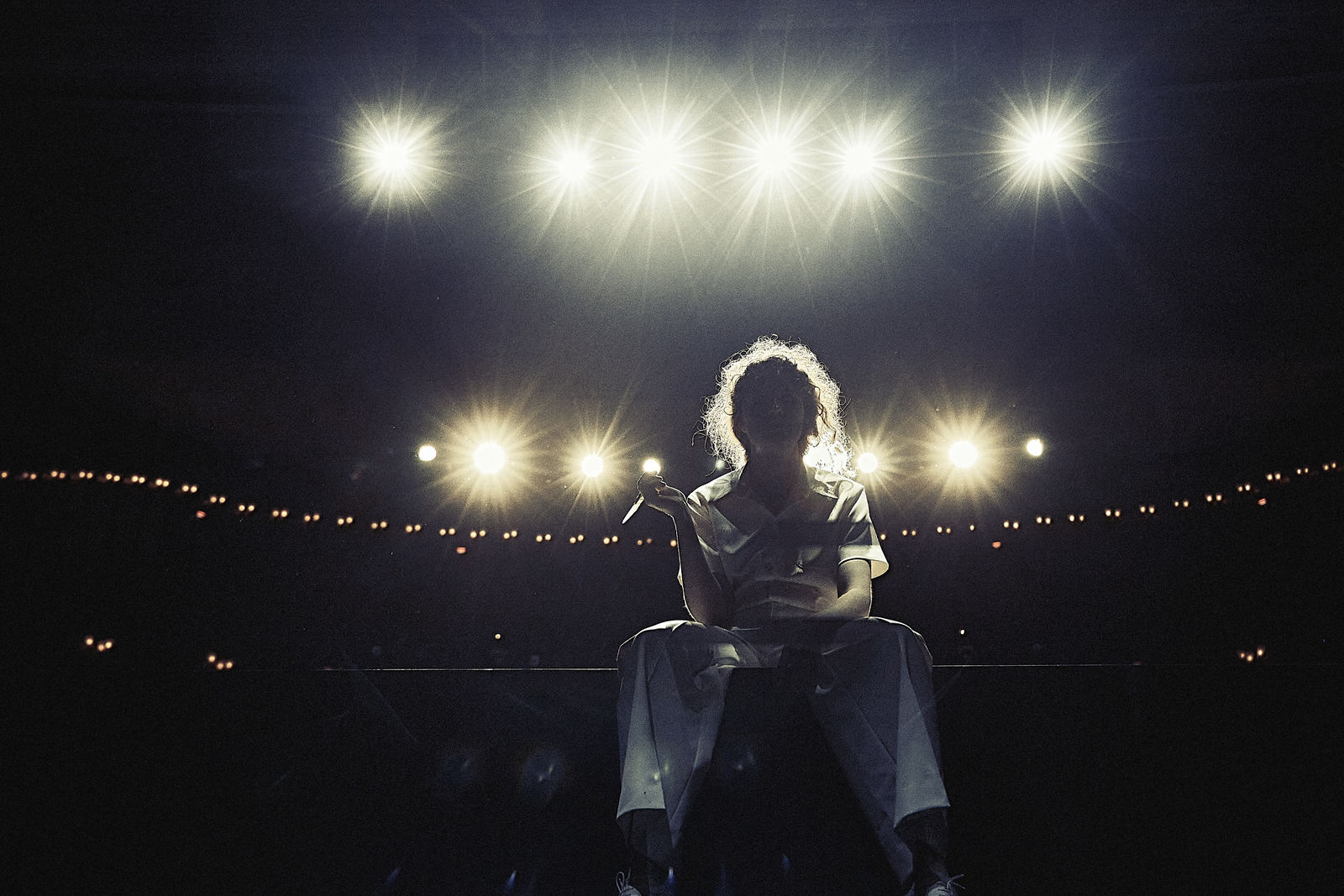

Steven Scharf

© Marcel Urlaub

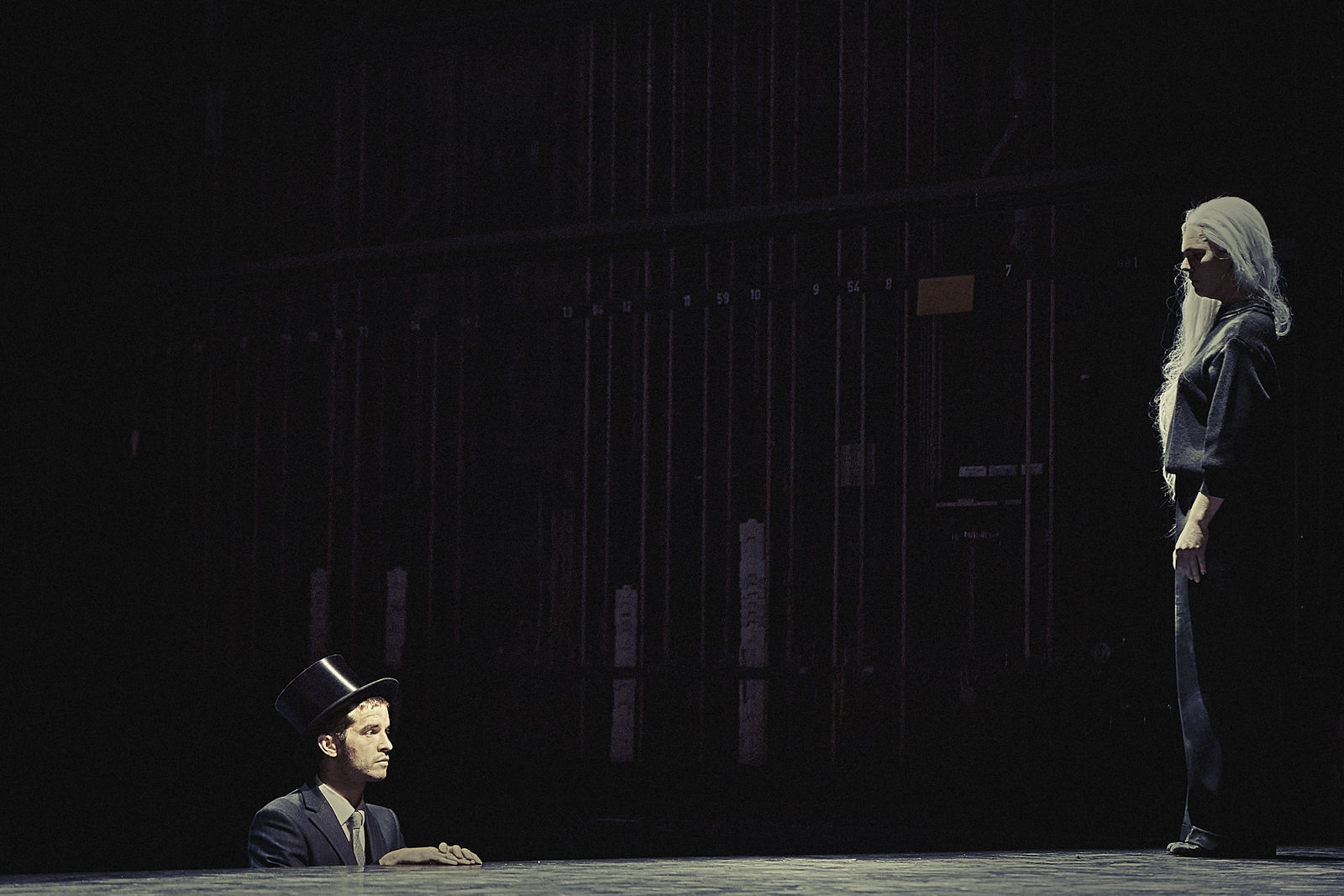

Jing Xiang, Steven Scharf (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Karin Moog

© Marcel Urlaub

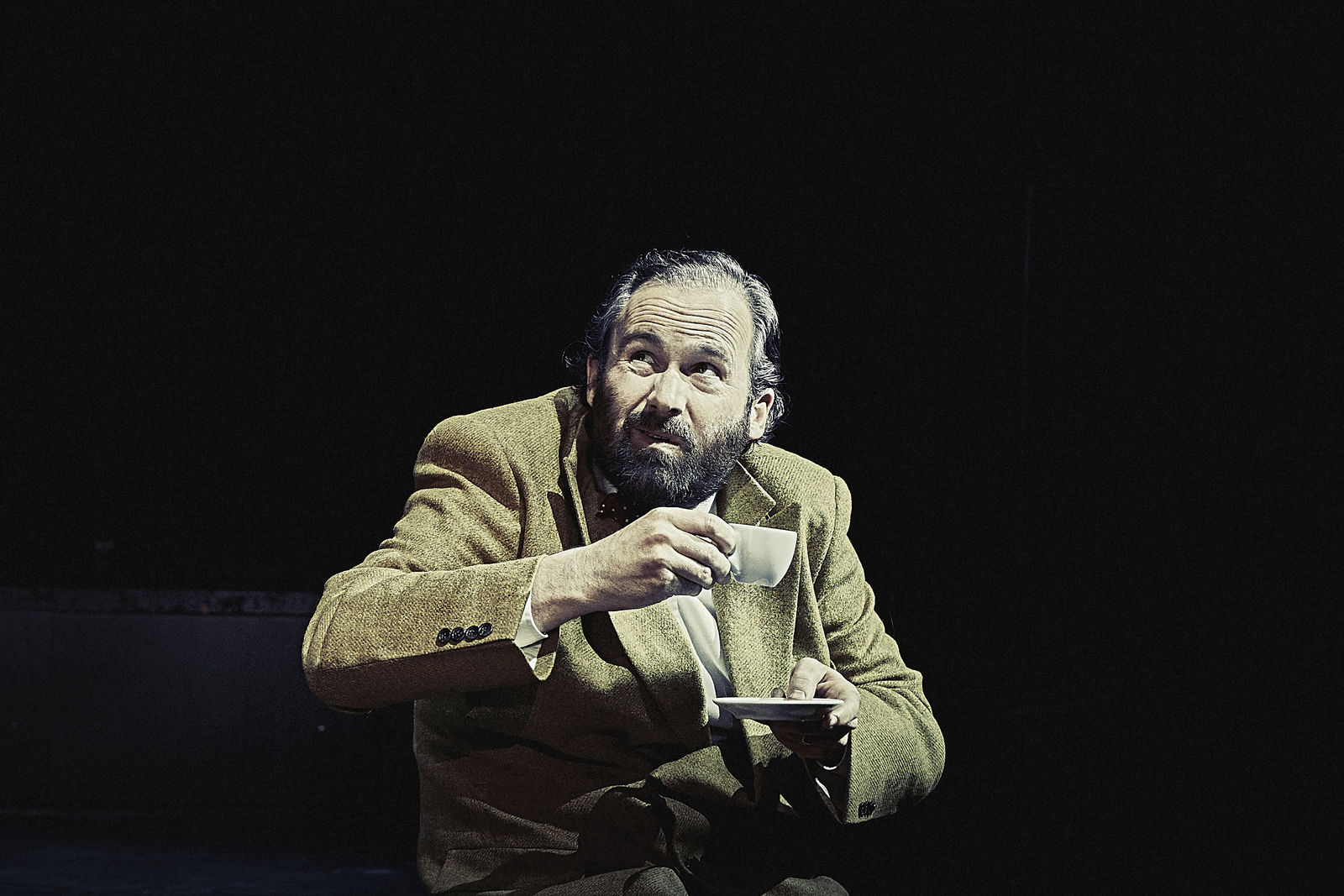

Guy Clemens

© Marcel Urlaub

Jing Xiang

© Marcel Urlaub

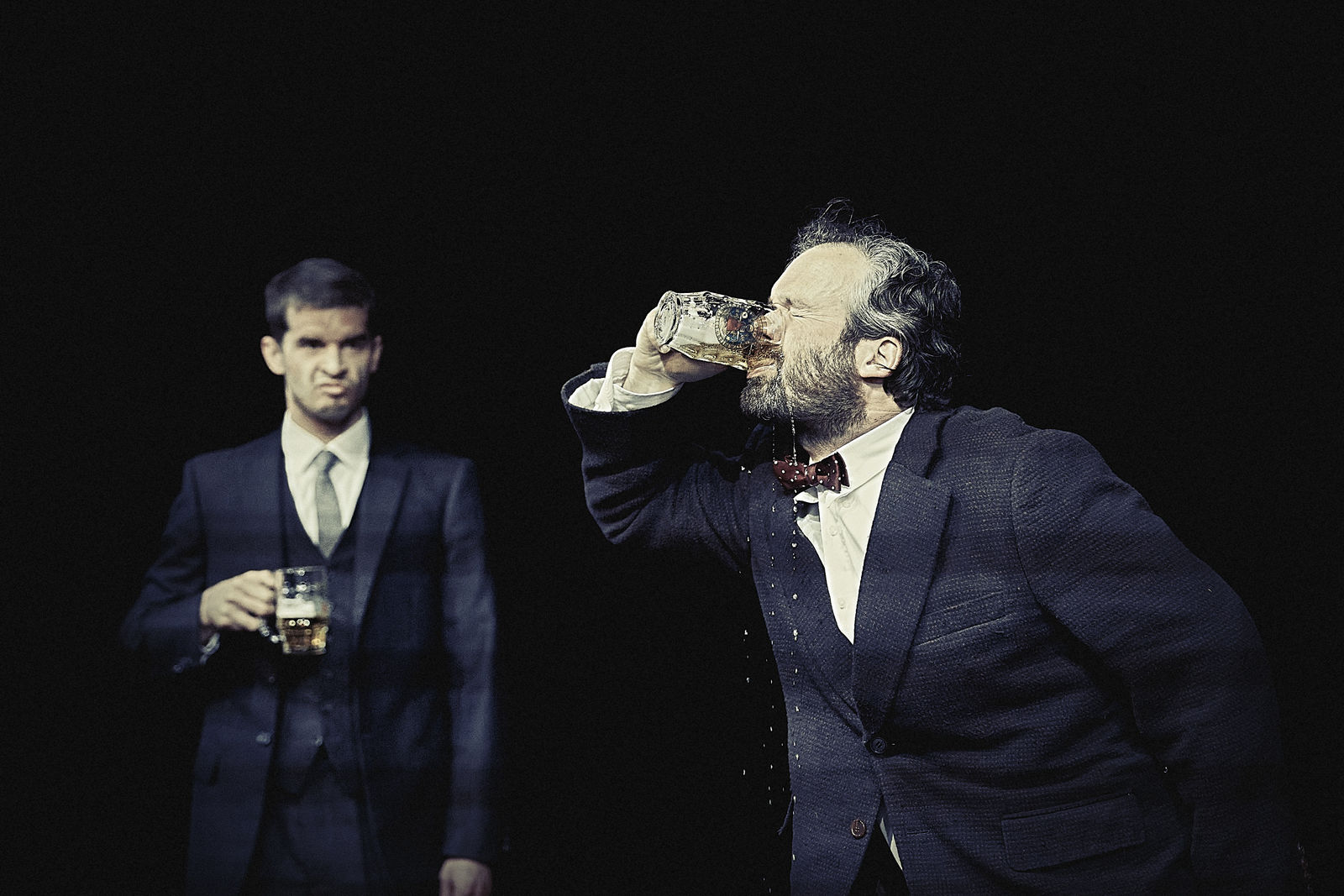

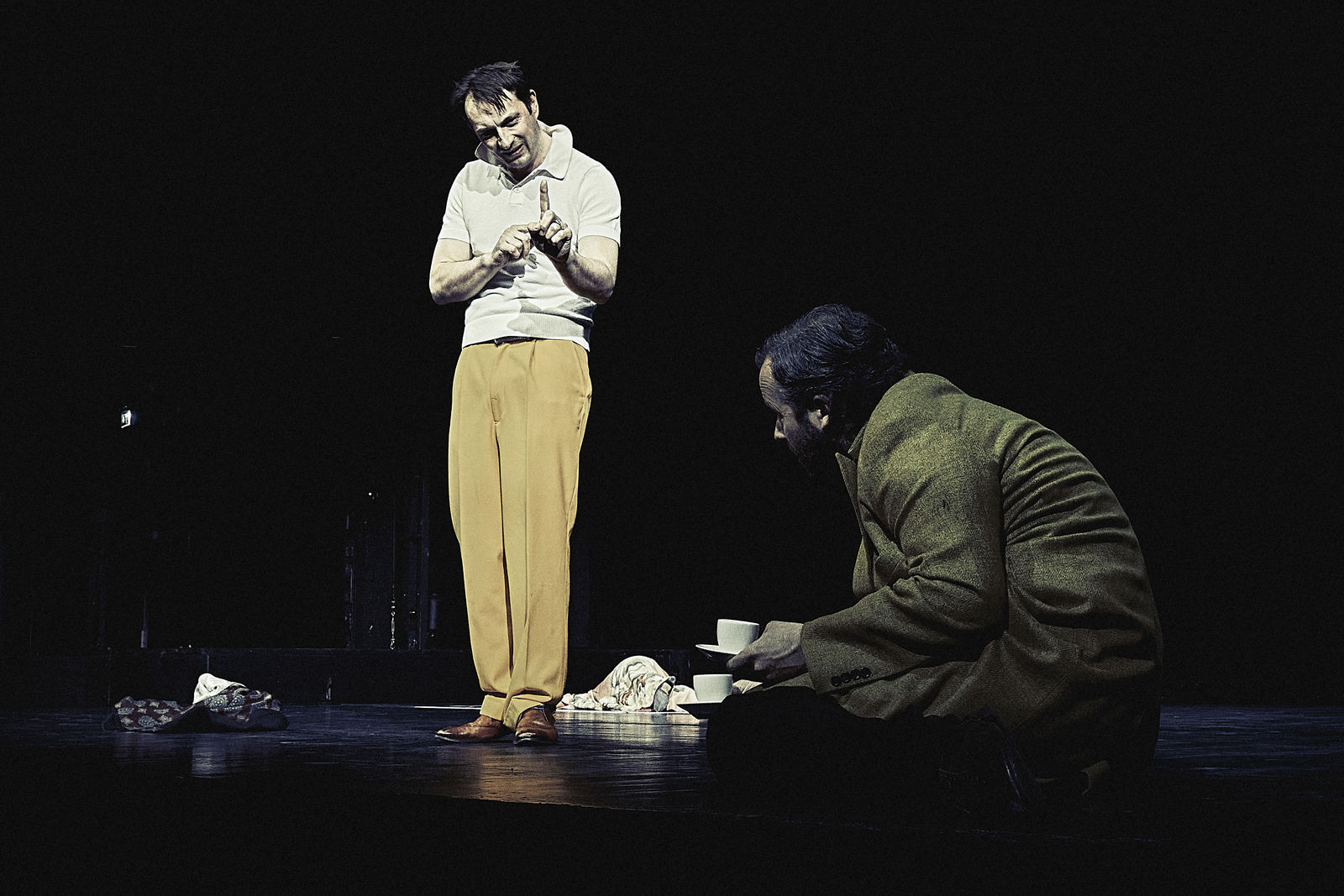

William Cooper, Guy Clemens (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Anne Rietmeijer, William Cooper (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

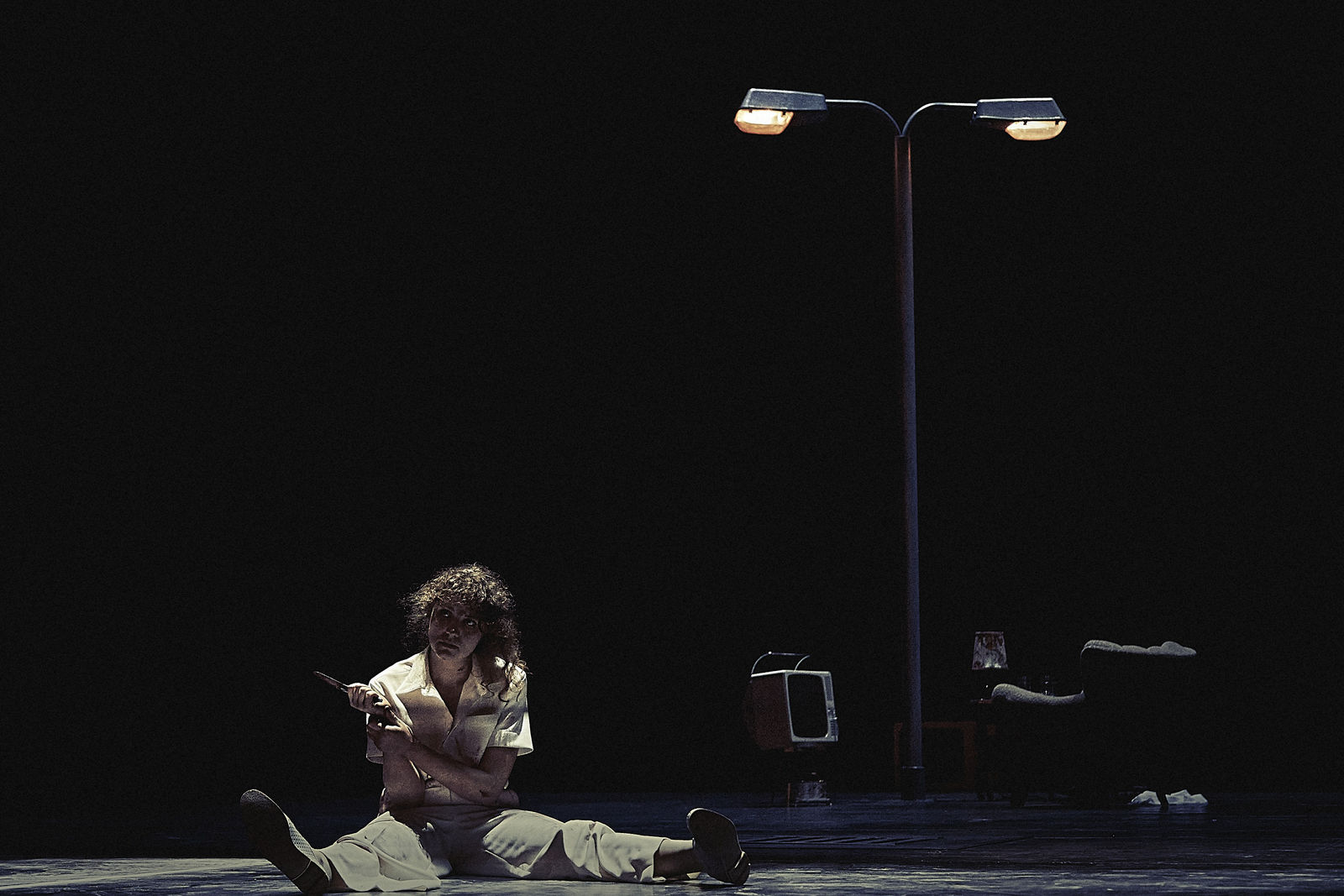

Anne Rietmeijer

© Marcel Urlaub

William Cooper

© Marcel Urlaub

Guy Clemens

© Marcel Urlaub

Anne Rietmeijer

© Marcel Urlaub

Jing Xiang

© Marcel Urlaub

William Cooper, Karin Moog (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Anne Rietmeijer

© Marcel Urlaub

William Cooper

© Marcel Urlaub

Steven Scharf, William Cooper, Guy Clemens (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

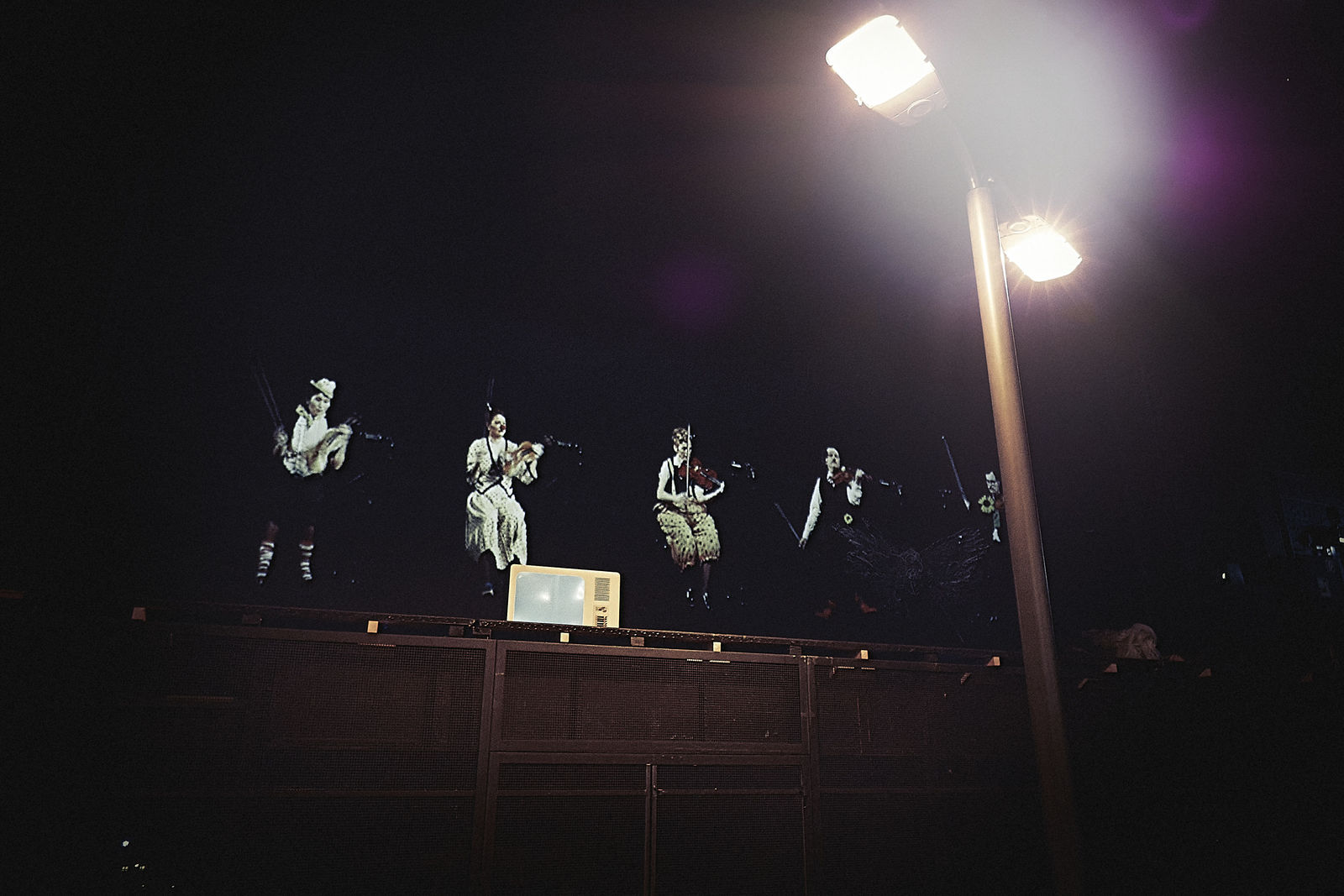

Bochumer Symphoniker

© Marcel Urlaub

Steven Scharf, Anne Rietmeijer (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Steven Scharf, Guy Clemens (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Guy Clemens, Steven Scharf (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Steven Scharf, Guy Clemens (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

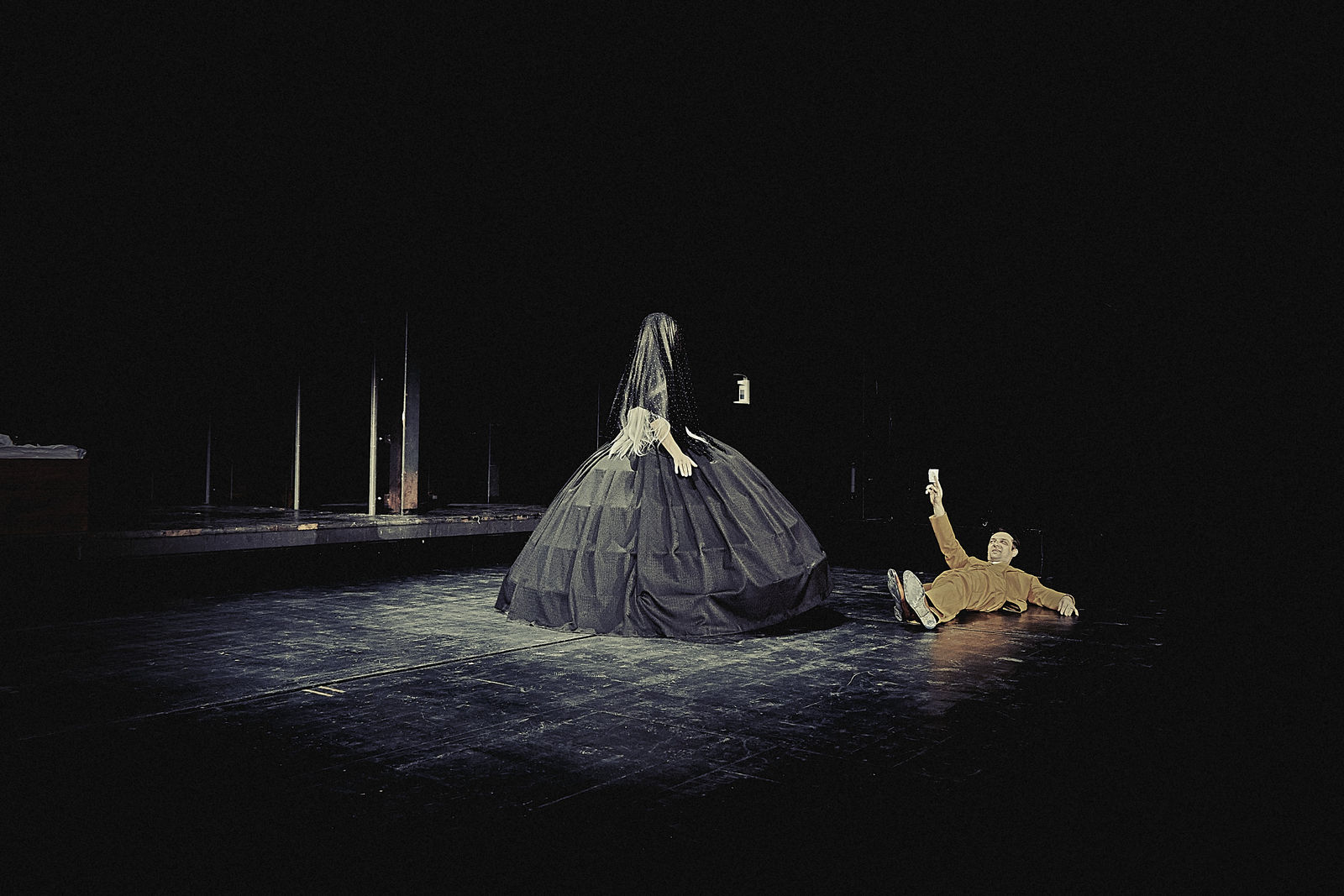

Karin Moog, Steven Scharf (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Guy Clemens, Steven Scharf, Anne Rietmeijer, Jing Xiang (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Guy Clemens, Jing Xiang, Steven Scharf (v. li.)

© Marcel Urlaub

Steven Scharf

© Marcel Urlaub

Press reviews

Press voices

[...] eine eigenwillige, exakt gearbeitete Inszenierung, die immer wieder Rhythmus, Tonfall und Charakter wechselt, die den Herrenmenschen im Clown und den Clown im Herrenmenschen freilegt [...]

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Hubert Spiegel

Johan Simons entdeckt in der Hauptfigur von Knut Hamsuns Roman einen Typus für die Gegenwart.

nachtkritik.de, Gerhard Preußer

Herausragendes Schauspielertheater.

Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Jens Dirksen

More press voices

Man genießt ein Gesamtkunstwerk aus Bühnenbild, großer Schauspielkunst des sechsköpfigen Ensembles und von Carl Oesterhelt eigens komponierter Musik, die von auf die Wände projizierten Bochumer Symphonikern großartig interpretiert wird.

Ruhrnachrichten

,

Max Kühlem

So verbindet der Abend Undurchsichtigkeit und Unberechenbarkeit mit abgründigem Witz und unaufdringlichem existenziellen Pathos. Man sollte diese eigenwillige Erfahrung nicht verpassen.

Westfälischer Anzeiger

,

Ralf Stiftel

Cooperations

Cooperations